JayJay Interview

In November 2025, Indonesian online education platform JayJay was recognized in the HolonIQ Southeast Asia EdTech Top 50 international ranking for the third consecutive year. The list recognizes the most promising startups in the region’s edtech sector.

«It’s difficult to get into this prestigious ranking, and even more difficult to stay there for three years in a row. We are one of the few companies in the region that has managed to do so for three consecutive years,» JayJay’s representatives said. At the same time, in a separate article on the HolonIQ website, the company was highlighted as one of the key drivers and innovators of edtech in Indonesia, specifically in the field of «workforce and skills solutions.»

Although JayJay is essentially an Indonesian company, it was created and is being developed by Ukrainians. Interestingly, this has become a marker of trust for young Indonesians. Ukraine is in Europe, and Europeans are seen as trustworthy.

JayJay currently employs 50 people. The startup is profitable and experiencing year-over-year growth of 30–50%. CEO and founder Vitalii Somka spoke with Scroll.media about how the company achieved this growth and what comes next. We started in 2021. I invested $250,000 in the launch.

We started in 2021. I invested $250,000 in the launch.

However, the official launch was in May 2022. It took approximately 10 months to establish the legal structure, assemble the team, develop the initial products, and hire key employees in Indonesia.

On the second day after launch, we made our first sale, which was $350.

After that, revenue continued to grow every month. Four months after launch, Jooble led a $1 million seed round. There were no other investors.

We do not plan to raise investment in the short term. In the long term, it’s possible. However, raising money at this time is challenging.

Why Indonesia?

The edtech market in Ukraine is more mature and well-established. There are five major players that control about 90% of the market, while roughly 30 smaller companies share the remaining 10%. The Indonesian market is about five years behind Ukraine’s, although we are closing that gap every year.

Indonesia will follow a similar path, with the top 3–5 players capturing 90% of the market. Our goal is to be among those 3–5 leaders.

When we started, there was no ChatGPT, so we immediately hired English-speaking Indonesians.

We initially brought in lecturers to create the first courses, along with sales and support specialists, on a part-time basis. Over time, they transitioned to full-time roles as we scaled step by step. Marketing, technical support, and management were handled by the Ukrainian team. Over the years, we’ve built a strong local team.

Today, in the age of AI, it’s fast and easy to review and verify all content in Indonesian.

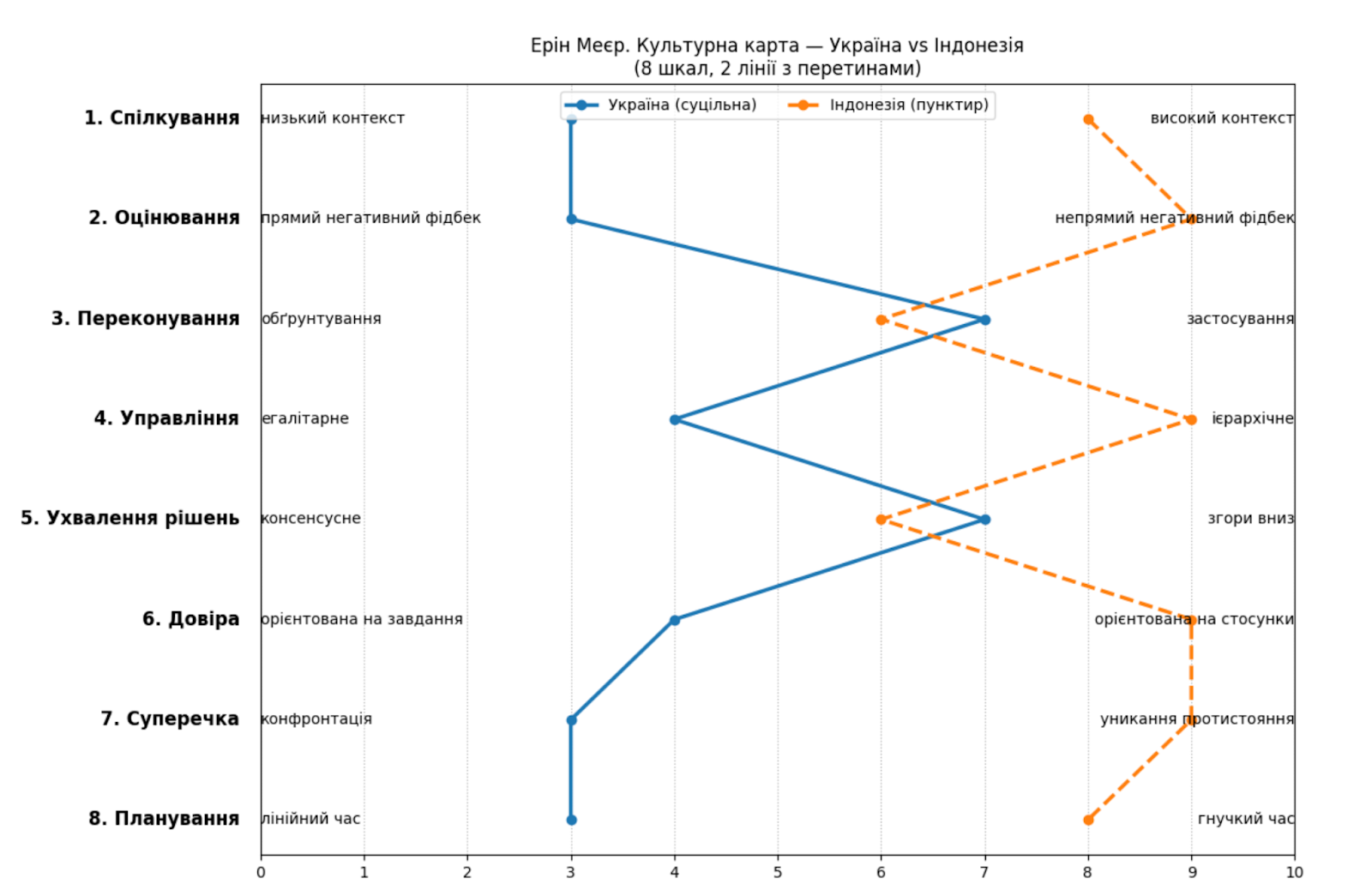

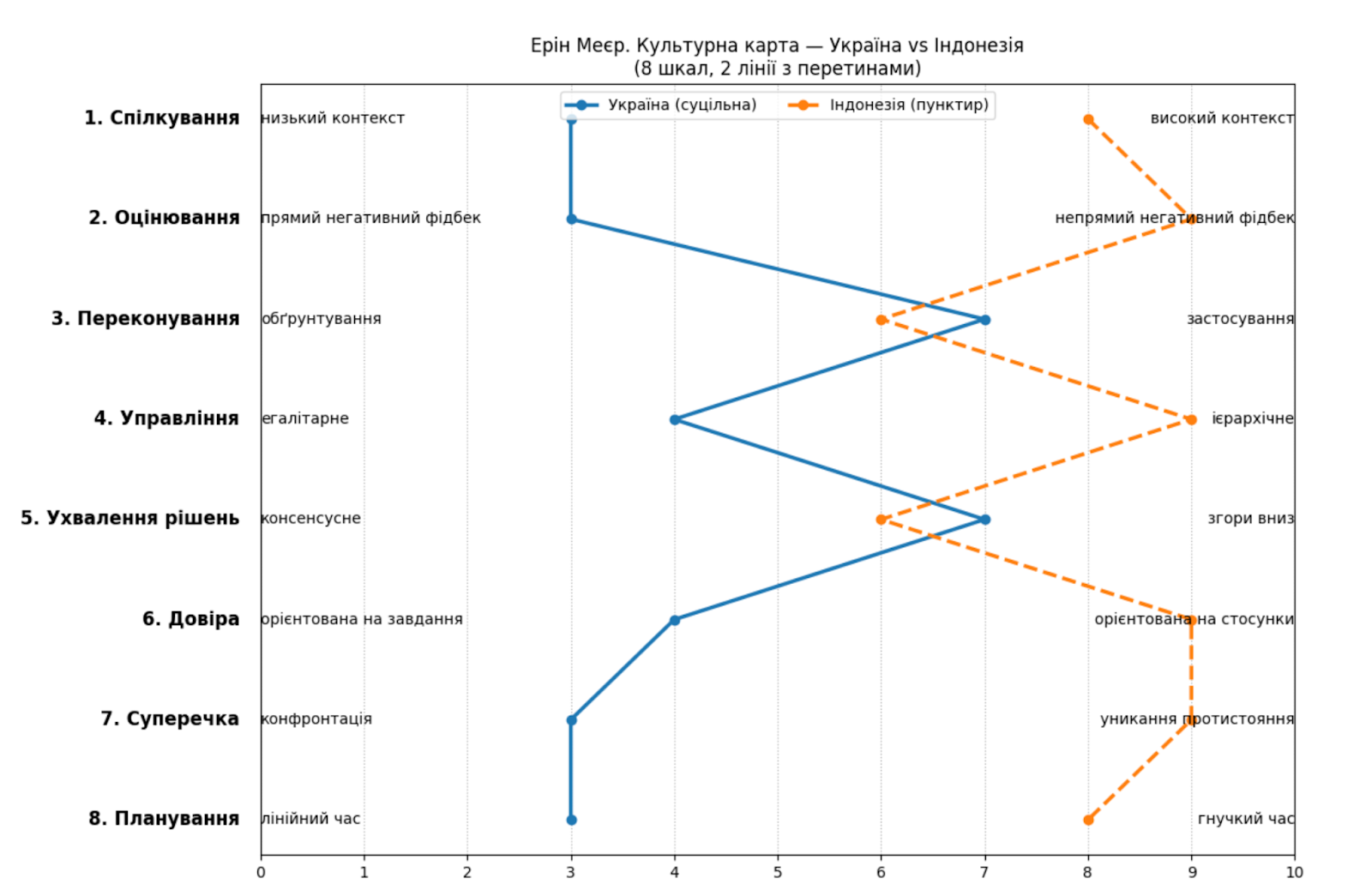

There’s a great book by Erin Meyer called «The Culture Map.» I recommend it to anyone planning to expand beyond Ukraine. Even people who already work in multiple geographies will find it valuable. Our team actually read the book much later, after we had already launched in Indonesia.

We made many mistakes in hiring and communication. Indonesian and Ukrainian business cultures are very different.

In Indonesia, communication is more indirect and contextual, with an emphasis on harmony and avoiding direct criticism. Ukrainians, by contrast, tend to communicate directly and expect open, straightforward feedback.

Ukrainian business culture places a greater emphasis on initiative, rapid problem-solving, and horizontal discussions, whereas Indonesian culture prioritizes respect for seniority, consensus, and formal hierarchy.

These differences aren’t better or worse — they’re simply different, and they require an adapted management and leadership approach. We’ve spent several years learning how to work effectively with Indonesian employees.

We initially started with a live course model. Problems emerged toward the end of October, when the rainy season began.

Indonesia has two seasons: dry and rainy. We entered the market at the start of the dry season.

The live format meant forming a group over two months, launching the course on a fixed date, and holding all classes live on a strict schedule — for example, twice a week, Wednesdays and Fridays at 7 p.m. We worked this way for about six months and saw solid early traction.

Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands, with the population unevenly distributed. Even on Java, the most populated island, many people live in small towns and villages.

During the rainy season, internet quality drops sharply: outages, lag, and complete disconnections are common. In more remote regions, power outages also occur.

This was a completely unexpected factor for us. Some students were unable to attend live classes consistently.

We began recording lessons, sending replays, and trying to compensate for missed sessions. However, the rainy season lasts nearly half a year, and operating in this manner became extremely difficult.

The most painful situations occurred when instructors themselves lost internet or electricity and were physically unable to conduct classes. We had to reschedule lessons, negotiate new dates, or extend course durations — all of which increased costs.

At that point, the unit economics stopped working.

In addition to internal challenges, we faced external ones as well.

In October 2023, tax authorities informed us that, starting November 1, we would become VAT payers. That meant an additional 11% added to the product price. This was completely unexpected. We hadn’t factored it into our financial model and had failed to track the revenue threshold that triggers VAT status. Had we known earlier, we could have prepared. Instead, it came as a shock.

When we began raising prices, it became clear that neither the team nor the market was ready. So we increased prices very gradually, spreading the 11% over time to make it affordable for customers and psychologically acceptable for the sales team.

For the Indonesian market, these are very sensitive changes. It took about six months to fully adapt.

At the same time, we realized that the live course model simply didn’t scale.

Each launch required assembling a group in advance, while we were actively testing different marketing hypotheses and creatives. Sometimes campaigns were successful, and sometimes they weren’t. Instead of the 50 students needed for economic viability, we sometimes enrolled only 15–18, while still paying instructors in full.

After six months, we completely abandoned live courses, rethought the product, and pivoted to a pre-recorded model. All theory was recorded in advance, and learning became asynchronous: students could join anytime after payment.

This was our first pivot. Within a few months, we were profitable.

Growth accelerated immediately after switching to pre-recorded upskilling courses for the creative industries.

- Unlike Ukraine, Indonesia doesn’t have a large outsourcing market, so demand for IT professions is lower. But demand for creative skills is growing rapidly.

- Indonesia also has a much younger population. Pre-recorded courses resonate far better with this audience. Live courses appeal more to millennials — the format that defined edtech 10 years ago. Our model is better suited to Generation Z.

As a result, we’ve been growing at a rate of 30–50% year-over-year for the past two years. Everything we earn is reinvested in development.

This model wouldn’t have worked in Ukraine. Why?

- First, timing. Indonesia was five to ten years behind Ukraine in the creative and IT industries. That allowed us to see several steps ahead in EdTech development and move quickly.

- Second, investment gave us time to test, pivot, train the team, and truly understand market needs.

- Third, we listened closely to customers and local employees. Their feedback and our observations of what worked and what didn’t shaped the model that ultimately succeeded. We didn’t invent anything from scratch; customers told us what worked.

- The team carried the project forward «despite,» not «thanks to.» Indonesia is our only market. If we fail here, we fail completely. That makes perseverance during the hardest moments critical. The game ends only when you leave the table.

- We didn’t hide that we were from Ukraine, but we didn’t actively communicate it either. Once, during a dinner after work, local salespeople told us they always say JayJay was launched by a European team. For them, Ukraine is Europe. Europeans are associated with taste, expertise, professionalism, and therefore trust. After that, we began positioning ourselves as a European school everywhere: in the media, on social networks, and on our website. This became a powerful differentiator from local competitors. We are different. We are European. And European means quality.

Recently, tax authorities visited us again — this time because JayJay is now among Indonesia’s top 20 edtech companies by revenue.

According to them, we had been operating at this level for some time but were not previously «on their radar.» As a result, we were moved into a category with extended reporting requirements.

Now we must submit detailed quarterly reports — not only on cash flow, but also income structure, number of students, individual courses, payment amounts per product, website traffic, and more. There are also product, marketing, and technical reports.

This places a significant burden on finance and leadership teams. Every quarter, accounting must gather data from all departments. It’s time-consuming, but we see it as part of business maturity.

We didn’t expect this level of scrutiny, even given that we’re already among Indonesia’s top ten education platforms by traffic. At times, it feels like Indonesia is approaching Western Europe in terms of bureaucracy, despite lagging behind in many other areas.

Today, we have more than 50 specialists: 12 Ukrainians and 40 Indonesians.

In Ukraine, we employ managers, developers, product specialists, marketers, and analysts. In Indonesia, we have sales teams, support staff, course producers, designers, content creators, and social media specialists.

Over the past year, the team has grown by 18 people. Open roles in Ukraine include Meta media buyer, Head of B2B Sales, and SEO specialist.

Next year, we plan to grow by 50% in Indonesia.

We will expand our educational product portfolio and enter new areas. In 2025, we launched a new format — mini courses. In 2026, we’ll continue to search for a strong product–market fit for this format. We are also entering B2B sales.

Launching a New Market in 2026

Every market has its limits. This is especially true in the edtech sector. At some point, further growth means competing with yourself, and gaining an additional 1% of market share costs more than it brings in profit. Until that moment arrives, entering a new market isn’t an option — it’s a necessity.

Edtech benefits from economies of scale. The larger you are, the more effectively you can control costs, optimize processes, and strengthen your team. The faster you scale, the harder you are to replicate.

And finally, dependence on a single country is a vulnerability — especially in an era of geopolitical instability.

JayJay Interview

In November 2025, Indonesian online education platform JayJay was recognized in the HolonIQ Southeast Asia EdTech Top 50 international ranking for the third consecutive year. The list recognizes the most promising startups in the region’s edtech sector.

«It’s difficult to get into this prestigious ranking, and even more difficult to stay there for three years in a row. We are one of the few companies in the region that has managed to do so for three consecutive years,» JayJay’s representatives said. At the same time, in a separate article on the HolonIQ website, the company was highlighted as one of the key drivers and innovators of edtech in Indonesia, specifically in the field of «workforce and skills solutions.»

Although JayJay is essentially an Indonesian company, it was created and is being developed by Ukrainians. Interestingly, this has become a marker of trust for young Indonesians. Ukraine is in Europe, and Europeans are seen as trustworthy.

JayJay currently employs 50 people. The startup is profitable and experiencing year-over-year growth of 30–50%. CEO and founder Vitalii Somka spoke with Scroll.media about how the company achieved this growth and what comes next. We started in 2021. I invested $250,000 in the launch.

We started in 2021. I invested $250,000 in the launch.

However, the official launch was in May 2022. It took approximately 10 months to establish the legal structure, assemble the team, develop the initial products, and hire key employees in Indonesia.

On the second day after launch, we made our first sale, which was $350.

After that, revenue continued to grow every month. Four months after launch, Jooble led a $1 million seed round. There were no other investors.

We do not plan to raise investment in the short term. In the long term, it’s possible. However, raising money at this time is challenging.

Why Indonesia?

The edtech market in Ukraine is more mature and well-established. There are five major players that control about 90% of the market, while roughly 30 smaller companies share the remaining 10%. The Indonesian market is about five years behind Ukraine’s, although we are closing that gap every year.

Indonesia will follow a similar path, with the top 3–5 players capturing 90% of the market. Our goal is to be among those 3–5 leaders.

When we started, there was no ChatGPT, so we immediately hired English-speaking Indonesians.

We initially brought in lecturers to create the first courses, along with sales and support specialists, on a part-time basis. Over time, they transitioned to full-time roles as we scaled step by step. Marketing, technical support, and management were handled by the Ukrainian team. Over the years, we’ve built a strong local team.

Today, in the age of AI, it’s fast and easy to review and verify all content in Indonesian.

There’s a great book by Erin Meyer called «The Culture Map.» I recommend it to anyone planning to expand beyond Ukraine. Even people who already work in multiple geographies will find it valuable. Our team actually read the book much later, after we had already launched in Indonesia.

We made many mistakes in hiring and communication. Indonesian and Ukrainian business cultures are very different.

In Indonesia, communication is more indirect and contextual, with an emphasis on harmony and avoiding direct criticism. Ukrainians, by contrast, tend to communicate directly and expect open, straightforward feedback.

Ukrainian business culture places a greater emphasis on initiative, rapid problem-solving, and horizontal discussions, whereas Indonesian culture prioritizes respect for seniority, consensus, and formal hierarchy.

These differences aren’t better or worse — they’re simply different, and they require an adapted management and leadership approach. We’ve spent several years learning how to work effectively with Indonesian employees.

We initially started with a live course model. Problems emerged toward the end of October, when the rainy season began.

Indonesia has two seasons: dry and rainy. We entered the market at the start of the dry season.

The live format meant forming a group over two months, launching the course on a fixed date, and holding all classes live on a strict schedule — for example, twice a week, Wednesdays and Fridays at 7 p.m. We worked this way for about six months and saw solid early traction.

Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands, with the population unevenly distributed. Even on Java, the most populated island, many people live in small towns and villages.

During the rainy season, internet quality drops sharply: outages, lag, and complete disconnections are common. In more remote regions, power outages also occur.

This was a completely unexpected factor for us. Some students were unable to attend live classes consistently.

We began recording lessons, sending replays, and trying to compensate for missed sessions. However, the rainy season lasts nearly half a year, and operating in this manner became extremely difficult.

The most painful situations occurred when instructors themselves lost internet or electricity and were physically unable to conduct classes. We had to reschedule lessons, negotiate new dates, or extend course durations — all of which increased costs.

At that point, the unit economics stopped working.

In addition to internal challenges, we faced external ones as well.

In October 2023, tax authorities informed us that, starting November 1, we would become VAT payers. That meant an additional 11% added to the product price. This was completely unexpected. We hadn’t factored it into our financial model and had failed to track the revenue threshold that triggers VAT status. Had we known earlier, we could have prepared. Instead, it came as a shock.

When we began raising prices, it became clear that neither the team nor the market was ready. So we increased prices very gradually, spreading the 11% over time to make it affordable for customers and psychologically acceptable for the sales team.

For the Indonesian market, these are very sensitive changes. It took about six months to fully adapt.

At the same time, we realized that the live course model simply didn’t scale.

Each launch required assembling a group in advance, while we were actively testing different marketing hypotheses and creatives. Sometimes campaigns were successful, and sometimes they weren’t. Instead of the 50 students needed for economic viability, we sometimes enrolled only 15–18, while still paying instructors in full.

After six months, we completely abandoned live courses, rethought the product, and pivoted to a pre-recorded model. All theory was recorded in advance, and learning became asynchronous: students could join anytime after payment.

This was our first pivot. Within a few months, we were profitable.

Growth accelerated immediately after switching to pre-recorded upskilling courses for the creative industries.

- Unlike Ukraine, Indonesia doesn’t have a large outsourcing market, so demand for IT professions is lower. But demand for creative skills is growing rapidly.

- Indonesia also has a much younger population. Pre-recorded courses resonate far better with this audience. Live courses appeal more to millennials — the format that defined edtech 10 years ago. Our model is better suited to Generation Z.

As a result, we’ve been growing at a rate of 30–50% year-over-year for the past two years. Everything we earn is reinvested in development.

This model wouldn’t have worked in Ukraine. Why?

- First, timing. Indonesia was five to ten years behind Ukraine in the creative and IT industries. That allowed us to see several steps ahead in EdTech development and move quickly.

- Second, investment gave us time to test, pivot, train the team, and truly understand market needs.

- Third, we listened closely to customers and local employees. Their feedback and our observations of what worked and what didn’t shaped the model that ultimately succeeded. We didn’t invent anything from scratch; customers told us what worked.

- The team carried the project forward «despite,» not «thanks to.» Indonesia is our only market. If we fail here, we fail completely. That makes perseverance during the hardest moments critical. The game ends only when you leave the table.

- We didn’t hide that we were from Ukraine, but we didn’t actively communicate it either. Once, during a dinner after work, local salespeople told us they always say JayJay was launched by a European team. For them, Ukraine is Europe. Europeans are associated with taste, expertise, professionalism, and therefore trust. After that, we began positioning ourselves as a European school everywhere: in the media, on social networks, and on our website. This became a powerful differentiator from local competitors. We are different. We are European. And European means quality.

Recently, tax authorities visited us again — this time because JayJay is now among Indonesia’s top 20 edtech companies by revenue.

According to them, we had been operating at this level for some time but were not previously «on their radar.» As a result, we were moved into a category with extended reporting requirements.

Now we must submit detailed quarterly reports — not only on cash flow, but also income structure, number of students, individual courses, payment amounts per product, website traffic, and more. There are also product, marketing, and technical reports.

This places a significant burden on finance and leadership teams. Every quarter, accounting must gather data from all departments. It’s time-consuming, but we see it as part of business maturity.

We didn’t expect this level of scrutiny, even given that we’re already among Indonesia’s top ten education platforms by traffic. At times, it feels like Indonesia is approaching Western Europe in terms of bureaucracy, despite lagging behind in many other areas.

Today, we have more than 50 specialists: 12 Ukrainians and 40 Indonesians.

In Ukraine, we employ managers, developers, product specialists, marketers, and analysts. In Indonesia, we have sales teams, support staff, course producers, designers, content creators, and social media specialists.

Over the past year, the team has grown by 18 people. Open roles in Ukraine include Meta media buyer, Head of B2B Sales, and SEO specialist.

Next year, we plan to grow by 50% in Indonesia.

We will expand our educational product portfolio and enter new areas. In 2025, we launched a new format — mini courses. In 2026, we’ll continue to search for a strong product–market fit for this format. We are also entering B2B sales.

Launching a New Market in 2026

Every market has its limits. This is especially true in the edtech sector. At some point, further growth means competing with yourself, and gaining an additional 1% of market share costs more than it brings in profit. Until that moment arrives, entering a new market isn’t an option — it’s a necessity.

Edtech benefits from economies of scale. The larger you are, the more effectively you can control costs, optimize processes, and strengthen your team. The faster you scale, the harder you are to replicate.

And finally, dependence on a single country is a vulnerability — especially in an era of geopolitical instability.